We have all heard the myth.

It appears on fire service websites all over the the U.S. and Canada. The Maltese Cross became the fire service symbol by way of the Knights Hospitaller, who, in true Disneyesque fashion, battled flames with their own smouldering robes, honorably fought off hordes of Barbarian Arabs with only their swords, expertly treated burned comrades, all while helping little old ladies across the street. They would have gotten the girl too… but alas, they were monks. They then became the noble Knights of Malta after the crusades, then the Order of St John, the ambulance service of England. Somehow that then transformed into the Firefighter’s Cross we identify with today.

The problem, of course, it that this is all just a fable, and not even a very good one. No one knows who invented this story, but it was created from whole cloth. It has been embellished endlessly, changing over time, as has the symbol itself.

The real story is both more interesting and more “American”.

The Real Knights Hospitaller

A significant part of the myth is based on a mistranslation and misunderstanding of what a “Hospital” or more properly “Hospice” was during the time of the crusades. The word, which derives from the latin for hospitality, actually meant what we would call a hostel now, or maybe a medieval cheap motel. What the forerunners of the hospitallers (who were black robed Benedictine monks) ran was inexpensive inn, a place to rest for travellers on their way to Jerusalem. It was not a medical facility. They were monks, not doctors. What they offered was a bed, water, food and prayer.

Rather than Johnny and Roy rushing you off to Rampart Emergency, The original role of the Knights Hospitaller was the equivalent of a security guard at a cheap hotel.3

The Order of St. John was formed by Papal orders in 1113 C.E., separating them from the original Benedictine monks. While they retained their black robes, they now had official status as a separate order.

Under their second grand master, Raymond du Puy, their role expanded to providing security to their guests travelling between their hostels. This is the origin of the “Knights”. Du Puy organized a militia of unattached secular knights1 and common soldiers in about 1120 C.E. to do the job. This militia took on the Standard of their financial sponsors, the merchant kingdom of Amalfi, Italy, who provided their early funding, simply adding it to their traditional black robes. The Amalfi standard was four arrowheads arranged with their tips touching to form a cross-like symbol.

Du Puy’s militia was later hired out to the newly formed Kingdom of Jerusalem in return for lands and income. From security guards, they now became mercenaries, albeit somewhat religious ones, and continued in that enterprize until the time of Napoleon.2

No where in the historical record, in the scholarly works of historians, nor the tradition of the order itself exists any trace of an association with firefighting. In fact, they were much more likely to have used fire, delivered by flaming arrow, siege engine or fire ship, as a weapon than otherwise.

The Templar Knights

Of course, one of the many problems with the Maltese Cross myth is the shape of the cross itself. The four arrowhead shape has remained to this day. Even the earliest forms of the Firefighter’s Cross do not reflect this shape. If you like you myths knightley, The Firefighter’s Cross, or Cross pattée, is far more similar to the Templar Cross than to the Maltese. With their portrayal in modern books and movies as mystical heros, there is a certain attraction to using their symbols as a basis for our own.

Alas, the Templar Knights share a common history with the Hospitallers, though their martial recognition was slightly earlier than the Order of St. John. While the Maltese Knights eventually became the Land Barons of Europe, the Templars became its first bankers.

Unfortunately, there is no actual historical connection to the Fire Service, excepting of course, that their leaders were burned at the stake by the King of France in the 14th century. Phillip IV owed them a significant amount of money, and, being a King, when he did not want to pay his debt, he simply set them alight. Apparently firewood was easier to procure than gold.

Despite the similarity of shape, we could dismiss the Templar Cross out of hand if it were not for one very tenuous connection to the Fire Service:

The Father of the American Fire Service

Benjamin Franklin is generally acknowledged as the founder of the first true fire department in what would become the United States. Writer, Publisher, Scientist, Statesman, Co-author of the Declaration of Independence and Fire Chief, he was a man of a great many talents.

He was also, as were many of the founding fathers, a Freemason.

The Freemasons have long used Templar symbolism in their Rites. Franklin would have, as a high-degree mason, been very knowledgeable about such things and as a (very) educated man of his time been familiar with the historical Templars as well.

So, a Fire Service connection at last. The Father of the American Fire service, a Mason and a symbol the looks very much like the Firefighter’s Cross. Have we found the true story?

Again, No.

First, the Masonic Templar Cross may not have been designed until after Franklin’s death in 1790. Second, and more importantly, Franklin is not known to have ever used the symbol or anything similar. Ever. Not in connection with his Fire Company, nor in his Fire Insurance Company’s fire mark.

The English Connection?

Though born in Boston, it must be remembered the that Franklin was an Englishman and the original concept for his, and others, fire companies were drawn from those of Great Britain. The English model of the times was of fire brigades employed by the Insurance Companies to fight fires occurring in the homes and businesses of their clients. Set up after the great London Fire of 1666, these insurance companies provided Fire Marks to identified the property they insured.

Surely then, these fire marks reflect the Maltese Cross tradition. After all, the Order of St. John is active even today in England, providing the Ambulance service in London and elsewhere. Right?

They do not. Nowhere in any of the fire marks, English or American does the symbol appear. And THERE IS NO REASON THAT IT SHOULD.

Not only was there no historical connection between the Knights of Malta or the Order of St. John and firefighting, but the English Order of St. John itself had been disbanded by Henry VIII in 1540 during the Reformation. It had disappeared in England more than a century before the Great Fire, and even longer before the first English Insurance brigades. It was not restored in England for 350 years, until its current namesake was recognized 1887, as an ambulance service. Decades after the Firefighter’s Cross appeared in the United States.

In fact, the London Fire Brigade, formed just after the Firefighter’s Cross appeared in the U.S., and the subsequent fire services of Great Britain choose as their insignia an eight-pointed multi-rayed star, not any form of of a cross at all. (This may have been influenced by the fire mark of the Sun Insurance Company, who was one of the largest insurers in London.)

Again, though the sort of cross-like symbols are present in the forms shown as Insurance marks, they did not gain traction as Fire Service symbols in the ensuing years.

Okay, How About a Little Irish? The Celtic Cross

Some forms of the Celtic or St. Patrick Cross are so similar to the Firefighter’s Cross, that the word “Eureka” springs to mind. There is also some historical correlation that might support the idea of this being the basis for our symbol.

Beginning in 1845, about twenty years prior to the introduction of the Firefighter’s Cross, a great wave of Irish-Catholic immigration arrived in the United States impelled by the Great Irish Potato Famine.

A great many of these immigrants settled in the cities of the east coast, particularly in New York. One of the few “jobs” they could get was in the various volunteer fire companies of the city, who were often organized in concert with local ethnic gangs.

However, neither the gangs, the volunteer firefighters, nor even the Irish regiments formed during the civil war used the Celtic Cross as a symbol. The most prevalent symbol used was the Harp of the Irish Flag.

Though, as we shall see, the Civil War played a major role in the development of the Firefighter’s Cross, not even the Civil War Brigades formed from Volunteer Fire Companies used any sort of cross for their regimental symbols. The most common symbol used was we now call the firefighter scramble.

And, lastly, but more importantly, during the time of the creation of the Firefighter’s cross there was an overwhelming anti-Irish and anti-Catholic political bigotry in the United States, particularly in the east coast cities. There is little chance that ANY Catholic or Irish symbol would have been chosen to represent a public agency. (This also argues strongly against the whole Knights of Malta myth, since they too were a Catholic order.)

St. Florian Cross?

While this idea has some adherents, there is unfortunately, no such animal as a “St. Florian Cross”. A diligent search for examples of any cross, other than the common christian cross, associated with Florian here in the U.S. or in Europe, has failed to find even one exemplar.

St. Florian is the Catholic patron Saint of Firefighters (and brewers, which might be considered appropriate), but as above, a Catholic symbol would not have been chosen to represent the firefighters of the time.

This is kind of a chicken and egg question, but in this case, which came first is quite clear.

No symbol of St. Florian even remotely similar to the Firefighter’s Cross is found or referenced anywhere in history prior to the mid to late 20th century, when some St. Florian devotional medals began to be struck commercially by various manufacturers in the U.S. using the already widely recognized Firefighters Cross as a model.

“Eliminate all other factors, and the one which remains must be the truth“ – Sherlock Holmes

Sign of the Four, 1890

Order out of Chaos…. The Real Story of The Firefighter’s Cross

Mid-19th century firefighting in New York City was bedlam.4 One hundred and twenty four different volunteer fire companies operated in the City, many organized with political, ethnic or street gang affiliation. Violent street riots between the companies were common. Thievery by the volunteers was the rule. Arson for profit was part of their “business model”.

It got so bad that the Fire Insurance companies, who paid the losses both of the structures and stolen contents, strongly supported by the police, bitterly complained to the Governor of New York State. In 1865, the State of New York took control of all firefighting services in New York City and part of Brooklyn and formed the professional Metropolitan Fire Department, closing the problematic volunteer companies for good.

The transition was not an easy one. Lawsuits were filed and the State Supreme Court had to decide the case. The first year’s operations were marred by sabotage, arson, and blockades by the gangs and displaced volunteers.

The originally appointed fire commissioners were in over their heads. Along with serious problems in logistics, finance, and equipment, discipline was difficult.

Of the 576 original firefighters, over a third, 222, were seriously disciplined in the first year…

The act creating this Department required the selection of members of the force, so far as practicable, from the volunteer firemen of New York.

In carrying this section of the law into effect, the Department undoubtedly procured men having experience as firemen, but with this experience came undisciplined habits, incidental to a volunteer department, and prejudices not readily overcome.

Numerous instances have arisen requiring the exercise of discipline. In 258 cases charges have been made and examined ; 52 men have been dismissed from the Department, 11 have been fined ten days’ pay, 34 have been fined five days’ pay, 22 have been fined three days’ pay, 3 have been fined two days’ pay, 12 have been fined one day’s pay, 61 have been reprimanded, 7 have been exonerated or excused, 19 have resigned while under charges, 4 had judgment suspended, 1 dropped from roll without prejudice, 28 complaints dismissed, 4 officers reduced to ranks.

With a so many problems of discipline and integrating the firefighters into the new department, as well as creating a new esprit de corps, the sub-committee formed to decide on a new badge for the firefighters could not agree on a design. The first uniform regulations for the MFD omit it completely:

The uniform of the firemen while on duty consists of a dark blue suit of pilot cloth, red flannel shirt, and the old fire helmet. On ordinary occasions the members will wear a neat forage cap, of a similar pattern to the navy cap, with glazed cover. In front of the cap will be embroidered the initials “M.F.D.,” and the number of the company. Each member is required to be in uniform at all times, except when excused. The engineers will wear a white helmet, with gilt front, and on their forage cape is embroidered the word “Engineer,” in the form of an arch, and the letters “M.F.D.” beneath. The design is neatly made of gold bullion, similar to the style worn by Captains of police. The engineers are also constantly in uniform.

There’s a New Sheriff in Town

The insurance companies, aghast at the continuing disorder in the department, strongly lobbied for replacing the Fire Chief with a military man. They argued the the chief need not have a fire service background to lead the department, but needed more the ability to instill discipline across the ranks.

They didn’t get exactly what they asked for. They got more. Rather than replacing the chief, they replaced two of the fire commissioners, most notably the President of the Commision, with military officers.

Alexander Shaler, Civil War General, Commander of the New York National Guard and Medal of Honor recipient took over the role of President of the Fire Commissioners in 1867. The effect was immediate. Logistics and finance, woefully behind in their work, became orderly. He spearheaded a drive for order and discipline, created a training cadre, installed the military ranks that departments use to this day and got two years of overdue reports sent off to the legislature. Most importantly, for our purposes, he got the sub-committee for badges off the dime.

A Symbol chosen Specifically because it was unique and Not TRADITIONAL.

The process for designing a badge was rather more complicated than it might appear. The commissioners had easily reached decisions on badges for insurance officials, the press and even themselves, but were stalled on selecting a design for the firefighters.

Such badges were used for admission across the fire lines. The police, who controlled access, needed something easily identifiable at a distance, distinguishable from the myriad of badges and insignia previously held by the 124 volunteer companies, many of which had been counterfeited by criminal actors. The firefighters, drawn largely from those companies, also needed a symbol they could embrace within the new organization that did not draw from, or show preference for, any one of them. It could also not be associated with any specific religious or ethnic group as such distinctions were part of the previous battles between the volunteer companies.

With the arrival of General Shaler. the decision was quickly made. The new symbol would be that of the Civil War Union 5th Army Corps. (the symbols of the other army Corps were already in use, in one form or another.) Not because it had any association with the fire service, but because it didn’t. Simple in design, easily manufactured and different.

Like the corps symbols of the civil war, the badge was to be worn on the hat, not on the chest.

The new badge was hastily inserted into the general orders for the uniformed personnel:

The fatigue-cap shall be made of navy-blue cloth, eight-inch top ; band one and a half inches wide ; quarters one and a half inches high ; front of solid patent leather, bound one and three-quarter inches wide at center, with small white metal slide ; two chin-strap white metal buttons, same as those worn upon the sleeve of the coat, and to be furnished in the same manner ; lining of leather, to be sewed into the seam at top, and band-welt in the top and one in the bottom of the band. The device, a white metal Maltese [sic]5 cross, with the appropriate emblems of the Department in the center, the letters ” M. F. D.,” and the number (numerically) on the points, and placed in the center of the front of the cap. – General Orders Metropolitan Fire Department – Elisha Kinsland, Chief Engineer (Fire Chief). 1867

Metamorphosis

In 1870 the brief life of the MFD came to an end as the City of New York regained direct control of the fire department. While Commissioner Shaler remained on the Board and operationally nothing much changed, an immediate order was issued to change the name, markings, and insignia from “M.F.D.” to the now famous “F.D.N.Y.”

The badge, of course, was among the first things to need revision.

The new badge was almost certainly redesigned by Louis C. Tiffany, then a designer at his father’s Tiffany & Co. and an aspiring painter. Tiffany & Co. had been one of the first big supporters of the new professional fire department.6 While famous for jewelry and silver, they also struck medals and badges for the police and fire service. While retaining the cross of the original M.F.D. badge, he added the gentle curves to the exterior straight lines, one of the hallmark’s of Tiffany’s work. (One of Louis Tiffany’s early designs, for a police medal, is now the famous interlocking and gently curving NY insignia of the New York Yankees.)

When viewing it through the prism of more than a century it might seem to us old and traditional, but at the time it was not. By the standards of the day it was a bold, modern and unique design, a precursor to what became known as “Art Nouveau” . And it was categorically American.

Our Iconic Symbol – The Firefighter’s Cross.

Born out of the horrors and chaos of the American Civil War and the equally chaotic fire service of the time, the Firefighter’s Cross came quickly to symbolize the professionalization of the U.S. Fire Service…when firefighting became a craft, a science, even a way of life, and not just a hobby. When a firefighter could be trusted to respond and save your stuff, not steal it, no matter who you were, where you lived or who your insurance company was.

Like most things in the Fire Service, the Firefighter’s Cross had pragmatic origins, not mythological ones. It fulfilled a need for an immediately identifiable, unique symbol that said “Fire Service” and would not be confused with any other. It did not, in fact, COULD not, draw from any particular ethnic, religious or political symbols.

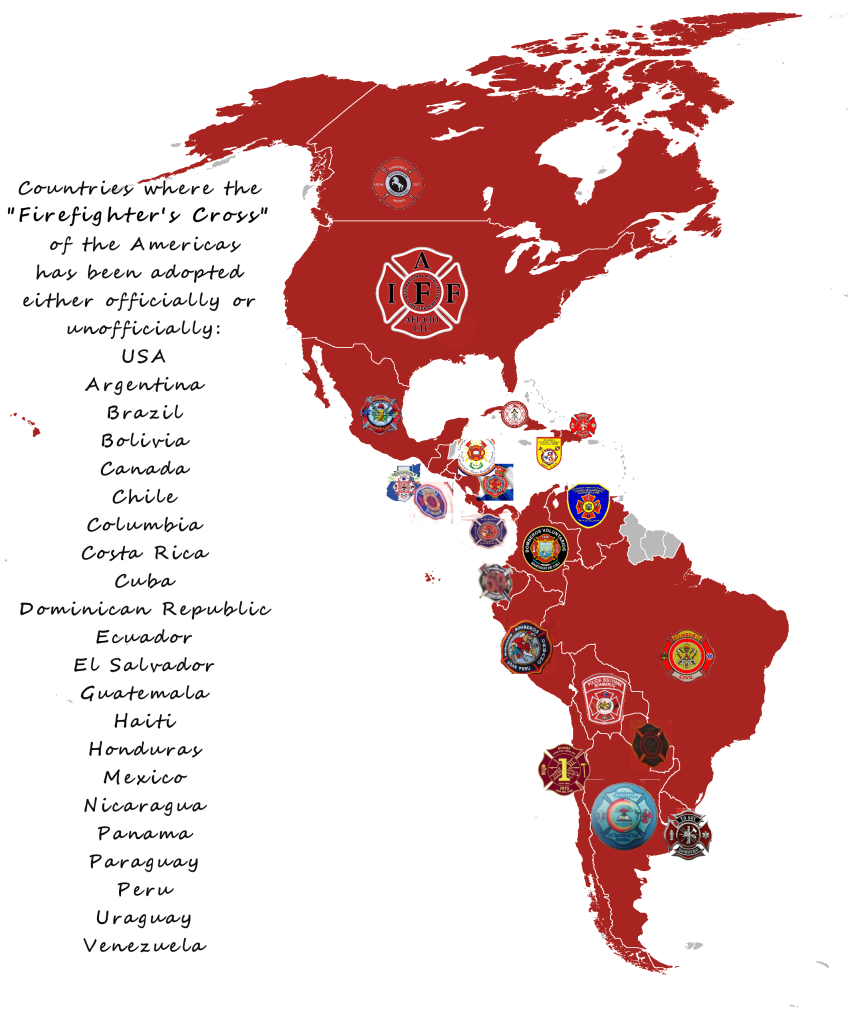

That fact, in and of itself, is probably the reason for it’s immediate popularity. Within a decade many of the east coast fire departments had incorporated the Firefighters Cross into their uniforms.7 Within the span of a single career, it spread from coast to coast becoming the symbol most associated with the Fire Service. Now, 150 years later, it covers the entire western hemisphere, and even in Europe it is recognized instantly as the symbol of the American Fire Service.

MEANINGS

As we have seen, the Firefighter’s Cross’ origin was utilitarian, not mystical. That doesn’t mean that a multitude of folks haven’t tried to assign meanings to various parts of the cross itself, largely in an attempt to shoehorn the insignia into a myth that it does not fit. The originators of the Firefighter’s Cross had no such intent. In fact, the the attempts of some to assign “values” to the points of the cross were drawn from stories of knightly chivalry that were themselves apocryphal.

Objectively, the Knights of the Crusades, including those of the Order of St. John, were an invading army, occupying by force land which was not rightfully theirs and killing or subjugating the indigenous peoples for their own profit. Hardly the symbology we would want for the fire service.

Looking to ancient Europe for American Fire Service symbology, as if we need to connect to some old world mythology to justify our pride, is both historically false, and overlooks the very things of which we should be most proud.

After all, the modern fire service is an American invention. When the fire brigades of London modernized in the 1880’s, it was the New York City model to which they came for expertise. When Chicago reorganized after the great Chicago Fire, it was General Shaler and his experience with New York they looked to. Throughout the western hemisphere, and much of the world, it is the U.S. fire service remains the example to emulate. It is our technical innovations they adopt, our training manuals they use, and our strategy and tactics they study. … and it is our symbol that they use to represent themselves. The Firefighter’s Cross is one of the very, very few United States symbols that has transcended international, political, racial and linguistic boundaries. Even in countries that are not terribly fond of the United States, the Firefighter’s Cross remains an instant admission card to any fire station in the hemisphere. Surely we can be at least as proud of that as any mythical connection to a black-robed French mercenary with poor hygiene habits.

If any ultimate meaning needs be assigned the Firefighter’s Cross other than the obvious, it should be that it is our version of “E Pluribus Unum” – out of many, one… the traditional motto of the United States and a pretty good metaphor for how the symbol actually originated.

Notes

1 The knights of the 11-12th century were an unsavory lot. Largely illiterate and profane men, they served as simply the heavy cavalry in the armies of the time. They held no royal standing or titles. Early Knights were generally oafish, considered rape and pillage their right as the spoils of war and caused considerable trouble in Europe. Most historians write that the Crusades were initiated more as a measure to export and control the knights rather than any kind of holy mission. However, they did train for many hours each day and for many years to acquire their martial skills. Monks, rather obviously, would not have been at all suitable in this role.

2 Du Puy did in fact reopen an old “infirmaria” much later in Jerusalem. It was run by the monk’s, not the knights, and treated illness, not battle injuries. Jerusalem had been taken a century before and was far from the battles. Battle injuries were treated by barbers, the surgeons of the day.

3 If you don’t know who Johnny and Roy are, ask an adult firefighter.

4 This scene is from Martin Scorsese’s “Gangs of New York” while a realistic depiction, it is short. For a much more detailed history read “The Gangs of New York“, by Herbert Asbury, the history from which the movie was derived.

5 Like most people today, the Chief Engineer misidentified the Cross pattee as a Maltese Cross, which of course it is not. This may be the root of our present day myth. My informal poll of random people in a local park found that 9 out of 10 people misidentified the outline as a Maltese Cross. The 10th identified it as the German aircraft symbol from WWII.

6 One of the first major fires the professional New York firefighters had was at Tiffany & Co. – “Upon one occasion the members of the department had complete possession for several hours of every part of the building containing the immense and valuable stock of jewelry of Messrs. Tiffany & Co. This firm made a public declaration that after a rigid investigation they had not missed a penny’s worth of their property, and gratefully acknowledged the protection afforded them. Under the old system Messrs. Tiffany & Co. would have been ruined.” Tiffany’ & Co. also struck the first, and still highest ranking, medal for valor of the MFD/FDNY , The Bennett Medal.

7 Further evidence of the provenance of the Firefighter’s Cross is revealed by the Commissioner of the Brooklyn Fire Department when they adopted the Firefighter’s Cross in 1882. “Commissioner Partridge has decided to make a change in the design of the badges of the Fire Department. The present badge is of nickel and in the form of a four-leaf clover. The new one is in the design of a Maltese [sic] cross , the old sixth [sic] army corps badge. Those of the Commissioner, deputy, chief engineer and assistants are gold-plated, and those of the privates are German silver. The present badges have been in use so long that some of them have found their way into the possession of parties who are not entitled to them, and from whom they cannot be obtained. Hence the change.” – The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Brooklyn, New York, 19 Sep 1882. While he does mistakenly identify the cross shape as “maltese”, he also verifies the origin of the symbol as an army corps insignia. Partridge also misidentifies the Corps as General Shaler’s 6th corps, with which he famously served at Gettysburg, rather than the correct 5th corps. This bolsters the evidence for the involvement of General Shaler, who he knew well, in the creation or as the instigator of the original firefighter’s cross.

Author’s Note:

I first became interested in the history of the Firefighter’s Cross more than twenty years ago, when I was still a company officer, after dubiously reading the somewhat absurd myth on the NFPA’s website. Having been a history major in college, with a specialty in 18th and 19th century U.S. History, there was much that did not ring true. Over the years, from time to time, I have renewed my research on the subject. While several other historians have touched on doubts about the myth, they have always done so apologetically and never directly contradicted the “official line” for reasons that escape me. The history and answers are there in plain sight, and are not particularly difficult to find. I call it the “Firefighter’s Cross” because that’s what it is, it is in fact, unique unto itself, and no other name really fits. It is NOT, and never has been a “Maltese Cross”, neither in shape nor in history.

It is long past time we called it something else.

Bibliography:

Our Firemen: A History of the New York Fire Departments, Volunteer and Paid, from 1609 to 1887 by Augustine E. Costello (1887)

Our Firemen: The Official History of the Brooklyn Fire Department, From the First Volunteer to the Latest Appointee Brooklyn Fire Department (1892)

New York Times Newspaper, New York, New York, November 3, 1865

Annual reports of the Board of Commissioners of the Metropolitan Fire Department., 1865-66 – Metropolitan Fire Department, (1867)

Annual report of the Metropolitan Fire Department of the City of New York., 1869.- Metropolitan Fire Department (1870)

Badges of the Bravest: A Pictorial History of Fire Departments in New York City by Gary R. Urbanowicz (2002)

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle Newspaper, Brooklyn, New York, 19 Sep 1882

The Knights Hospitaller By Helen J. Nicholson (2002)

The History of the Knights Hospitallers of St. John of Jerusalem, Styled Afterwards, the Knights of Rhodes, and at Present, the Knights of Malta Vols. 1-5 – Mons. L’Abbé de Vertot, (1775)

The Shield and the Sword: The Knights of Malta – Ernle Bradford, (1973)

The Templars. Piers Paul Read, (1999).

The Gangs of New York: An Informal History of the Underworld – Herbert Asbury (1928)

Five Points: The 19th Century New York City Neighborhood that Invented Tap Dance, Stole Elections, and Became the World’s Most Notorious Slum – Tyler Anbinder (2010)

Thomas Francis Meagher and the Irish Brigade in the Civil War

by Daniel M. Callaghan (2011)

Colonel Elmer E. Ellsworth, First Hero of the Civil War – Charles Anson Ingraham (1918)

Officers of the Volunteer Army and Navy who served in the Civil War, published by L.R. Hamersly & Co., (1893)

Extremely well written!!! I enjoy factual data and research without personal opinion (very hard to find these days.) Unfortunately, many would rather be ignorant and believe what they THINK is right rather than what is ACTUALLY right. Well done!

LikeLike

This was very interesting. I am not sure how well it wiil be received by the fire service. Change does not come easy to the fire service. Even when change is in our best interest.

LikeLike

“A hundred years of tradition, unimpeded by progress…” I agree, though I’ve had relatively little pushback on this issue. I think most people realize, when they think about it, that the apocryphal story that has circulated for the past 40 years or so was pretty silly.

LikeLike